September 25, 2022

The federal government is committed to reducing poverty in Canada and has established some concrete income-based targets against which progress can be tracked. In its 2018 Poverty Reduction Strategy, the federal government identified the CVITP as playing a role in helping it to meet those goals. This is because the CVITP helps low-income residents to file their income tax and benefit returns. And a return must be filed for a low-income person to gain and maintain access to many federal, provincial and territorial benefits which are income tested.

The income tax and benefit return is the key instrument the Canada Revenue Agency (CRA) uses to fulfill its two core responsibilities of administering the federal government’s tax and benefit systems. It integrates two complementary functions that determine at one and the same time the federal (and sometimes provincial or territorial) income taxes residents must pay and many of the federal (and sometimes provincial or territorial) benefits residents are entitled to receive.

Canadian residents with taxable income have a legal obligation to file a return. (Failure to do so can be considered tax evasion.) Similarly, it is part of the CRA mandate to identify and pursue those residents who have not filed a return to oblige them to file a return and pay any taxes (as well as interest and penalties) they owe.

But Canadian residents with no taxable income have no legal obligation to file a return. Similarly, the CRA is not mandated to identify and pursue those residents who have not filed a return to oblige them to file a return and receive any benefits to which they are entitled.

So what does the CRA do in this latter case, when a resident with no taxable income does not file a return and thus loses access to benefits that are contingent upon filing a return? The CRA could be passive and do nothing. Or it could actively pursue those residents to encourage (if not oblige) them to file.

We believe the federal government has a reasonable expectation that the CRA will not be passive but will actively encourage residents to file. This is because the federal government has identified so many of the benefits contingent upon filing a return as key to achieving the objectives identified in its Poverty Reduction Strategy. And as the federal government’s administrator of its system for filing returns, the CRA is thus the gatekeeper for gaining and retaining access to so many of these benefits.

An ambivalent attitude

The CRA’s current actions with respect to the CVITP suggest it has a highly ambivalent attitude toward the CVITP. Why do we say this? First, because we believe the CRA has adopted two approaches which, taken together, are contradictory.

On the one hand, the CRA wants an “arm’s length” relationship…

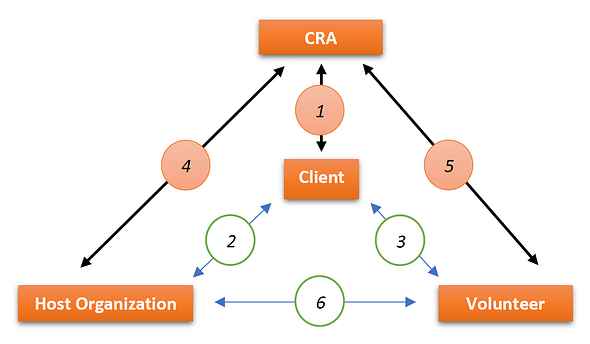

The CRA has repeatedly stated the importance of maintaining what it calls an arms-length relationship with CVITP host organizations (see 4 in diagram above) and their volunteers (see 5 in diagram). For example, on page 41 of the CRA Ombudsman’s 2020 report on the CVITP, the CRA states that it:

“…strives to provide as much support as possible to the volunteers and partner organizations, while maintaining the arms-length relationship required to mitigate the liability risks that would be associated with any prescribed involvement in tax return preparation by the CRA.”

Yet it is unclear what exactly the CRA means by an “arms-length relationship” in the CVITP context. On its own website, it defines “arms-length relationship” in terms that do not appear at all relevant to the CVITP.[1]

The CRA says it needs to maintain some distance from – or, to word it another way, not work too closely with – host organizations and their volunteers to mitigate any risks the CRA might run as a result of the returns these partners prepare for clients. It is unclear these risks are more significant than those the CRA faces in working with commercial operators who prepare returns for a fee.

The risks to the CRA seem to be more obvious with respect to the tax dimension of clients’ returns. For example, it is conceivable that the CRA could run into legal difficulties were it to both prepare a person’s return and subsequently challenge (through the assessment process) the amount of tax that person is legally obliged to pay. If the amount of tax paid by the person was subsequently questioned, the taxpayer could reasonably argue that they are not liable for any mistake as they were simply following the instructions of their tax preparer, the CRA. Thus, the CRA may wish to avoid the liability for any mistakes it could make in preparing people’s returns. This leaves it in a clear legal position to be able challenge what people claim to owe as taxes.

On the other hand, it takes on the risk of preparing some returns

The CRA clearly states on its website that it is prepared to do the returns of those residents with a modest income and a simple tax situation who have used a free tax clinic before or are eligible to use one (see 1 in diagram). Perhaps this is because the CRA believes that most of these people have little or no tax to pay. Thus, any mistakes the CRA might make in preparing returns are likely to be small in number and in their financial impact.

This looks like a contradiction

However, the CRA’s willingness to do the returns of low-income people and accept the risks this entails is puzzling. It seems to contradict the CRA’s own argument about the need to mitigate for the liability risks associated with its involvement in the CVITP return preparation process by maintaining some distance from its partners.

What about the link to the Poverty Reduction Strategy?

This contradiction is not the only reason we believe the CRA remains highly ambivalent about the CVITP. The main rationale for the CVITP in its early decades may have been simply to help low-income people who did not understand how to prepare their income tax returns and could not afford to pay someone else to do it. However, in the past decade in particular, the return process administered by the CRA has increasingly been recognized by the federal but also the provincial and territorial governments as an efficient way of assessing low-income residents’ eligibility for many income-tested benefits intended to reduce poverty.

Nevertheless, in the four years since the federal government’s publication of its Poverty Reduction Strategy (PRS), the CRA has never once publicly acknowledged the link the federal government has established between the CVITP and the PRS’s goals.

Drop the ambivalence…

Events over the last three years should shake the CRA of its ambivalence. Just as the CRA has seen its budget for the CVITP quadrupled with the aim of doubling its client numbers, it saw those numbers dip by a third from their peak. If the CVITP is to be turned around, the CRA must get off the fence and take more initiative. If the CRA wishes to retain control over the CVITP, it needs to start thinking more constructively and creatively about the supportive role it should play in working with its CVITP partner organizations and volunteers.

…or hand the administration to another group willing to be more supportive…

But if the CRA is unwilling to drop the unhelpful “arm’s length” position as a way of absolving itself from taking more concerted action, then it should seriously consider handing over the administration of the CVITP to another government agency or department such as Employment and Social Development (ESDC) Canada which could be more supportive.

…like ESDC

This is not as far fetched as it sounds. There are a number of reasons why ESDC may be a better home for administering the CVITP.

First, ESDC currently leads the federal government’s approach to the charitable and non-profit sector, as acknowledged in the government’s response in 2021 to Recommendation 22 of Catalyst for Change: A Roadmap to a Stronger Charitable Sector, the 2019 report by the Special Senate Committee on the Charitable Sector. The ESDC already administers some programs which build capacity within the charitable and non-profit sector. Thus, ESDC should be well informed about the financial constraints facing the charitable and non-profit sector more generally, and thus those within which the CVITP’s host organizations currently operate.

Second, ESDC has substantially more experience than the CRA in managing federal government grants and contributions to the charitable and non-profit sector. This is especially relevant for the provision of financial support to CVITP host organizations such as is the case with the current CVITP pilot grant program.

Third, one of the central benefits identified in the PRS which aims to reduce poverty is the Guaranteed Income Supplement, a benefit managed by ESDC. Given that filing a return is a pre-requisite for maintaining GIS eligibility, ESDC should appreciate the important role that the CVITP plays in helping many low-income seniors to continue to receive their GIS payments.

And finally, the Minister of Family, Children and Social Development, one of the four ministers who head up ESDC, has lead responsibility within the federal government for reporting on implementation of the PRS. Thus, ESDC should be well aware of the CVITP’s role in contributing toward delivering on the government’s PRS objectives.

In conclusion

We are not suggesting that the ESDC should take over responsibility for the CVITP. The CRA could continue to administer the CVITP. But only if it drops its ambivalent attitude and makes a concerted effort – ideally based on an explicit strategy, subject to monitoring and evaluation – to strengthen the CVITP.

[1] “The term “at arm’s length” describes a relationship where persons act independently of each other or who are not related. The term “not at arm’s length” means persons acting in concert without separate interests or who are related.” See https://www.canada.ca/en/revenue-agency/services/charities-giving/charities/charities-giving-glossary.html