We are proud to be able to provide all of the website content in both official languages.

Cliquez ici si vous préférez lire ce blogue en français.

We are proud to be able to provide all of the website content in both official languages.

Cliquez ici si vous préférez lire ce blogue en français.

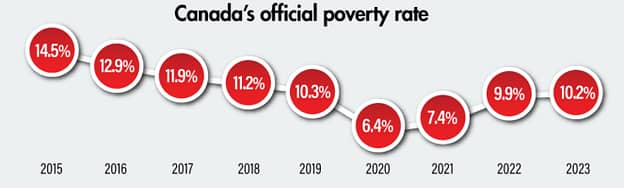

In the 2023 return filing season, the CVITP served only 25% of those living in poverty in 2022. The poverty rate in Canada rose from 9.9% in 2022 to 10.2% in 2023. What percentage of the 3,168,000 adults living in poverty in 2023 was served by the CVITP in the 2024 tax season?

Read this article to find out more. Also learn why the Canada Revenue Agency should be doing a lot more to expand the CVITP yet seems instead to be focusing its efforts on two other largely ineffective programs.

What is happening to the CVITP over time? The Canada Revenue Agency (CRA) has been publishing figures about the CVITP for some time. But it only began offering a consistent view of what is happening across the country in 2022 when it started publishing figures from the previous year on the CVITP pages. Even so, the CRA does not publish analyses of the data to show what has been happening over time.

I’ve been tracking the numbers since 2019. Each year, I update the CRA’s figures to show how the CVITP is evolving. With the recent release of the 2024 data, I have completed a review of the trends for the 2017-2024 period. This information is now available as a series of four short articles with supporting data tables and charts plotting the data. In these, I begin by looking at the results from delivering CVITP service. I present and analyze the numbers for people assisted, returns filed and value generated for clients. I then look at the infrastructure supporting CVITP service delivery. I present and analyze the numbers for the recruitment of volunteers and host organizations. Then I use two simple measures to examine volunteer and host organization productivity. Finally, I extrapolate from these trends to what will likely happen in the 2025 season. Read the summary of my findings as well as the full articles (with data and graphs).

Imagine receiving a Notice of Assessment that says you owe money when you were expecting a refund. Or again, receiving a notice for a benefit that contains an obvious error. A greater surprise might be to discover that your return has been filed without your knowledge. Unfortunately, these kinds of things happen all too often because a volunteer has failed to follow two important steps: review the results of the return with the client and then obtain their consent to file it.

In my visits to host organizations across Canada as well as in my own CVITP volunteer work with clients, I have been surprised by the large number of clients who are not being informed of what is contained in the completed return and whose consent is not sought before their return is filed.

This article explores how and why this malpractice is so widespread. It then spells out the reasons why the volunteer must get the client’s informed consent prior to filing their return.

A recent article looked at disparities in access to free CVITP services between the provinces in the 2021 tax filing season. This article updates the 2021 findings on inequalities of access to CVITP services across Canada for the 2023 tax filing season. The results are disappointing but contain at least one surprise. Read here to learn the results.

On February 28, 2025, the CRA announced that it was pushing back the deadline for all T slips issuers to electronically submit their slips until March 7, the end of the first two weeks of the income tax and benefit (ITB) return filing season. This meant that CVITP volunteers could not depend on the Autofill My Return (AFR) service to reliably provide all a client’s T slips. Anyone wanting their ITB return done in the first two weeks had to present paper T slips to their return preparer to make sure all their sources of income were declared. This article argues that this measure undermined the reliability of the AFR function and furthermore, that there were better ways to have implemented this.

On February 24, the CRA posted on its CVITP website that it is extending its pilot grant project for a fifth year. Grants of $5 will be paid for 2020 to 2024 tax year returns filed between June 1, 2024, and May 31, 2025.

The good news is that the CRA has managed to find some money to continue supporting the CVITP for another season. But this masks some less welcome news. Learn here what this means for the CVITP and this pilot grant project in the 2025 tax filing season.

As the 2025 tax season gets underway, I will be focusing on serving CVITP clients, like other volunteers, so there will be fewer blog postings during the March-April period.

2025 tax season information for volunteers: Essential information for volunteers as well as information that is good to know for the 2025 tax season have now been posted. Under the menu option “Tax Year”, look for “2024”.

Questions? If you have any questions or issues you would like to see addressed in future articles, please use the function on the “Contact Us” page to send a message. (I have a long list of article ideas but want to make sure I am writing on questions or issues that are relevant to volunteers and host organizations.)

Tell your friends! If you find this website useful, please share it with fellow volunteers and clinic coordinators at organizations that host CVITP clinics.

Why not subscribe? And finally, a reminder for those who are new to this website or visit it irregularly: if you find the website useful but forget to consult it periodically, you can sign up to the “Subscribe” function in the right-hand column. Except for articles posted on the provincial and territorial pages, every article is featured in a short blog posting (which includes a link to the full article). Subscribers automatically get notifications with every new blog posting together with pertinent links. (Please note that I do not share this mailing list with anyone.)

Every fall, the Department of Finance Canada provides an update informing the public about the state of the federal government’s finances and key economic development. The Fall Economic Statement (FES) for 2024 was issued on December 16. Intriguingly, it touched on the issue of filing the returns of low-income Canadians.

The articles in this two-part series tackle both what the FES said and what it did not say about this subject as the government’s omissions were as relevant to the CVITP as its treatment of the filing of returns for low-income Canadians.

The first article provided commentary on what the FES had to say about advancing its agenda for the automatic filing of low-income Canadians’ income tax and benefit returns. This second article highlights two areas of relevance to the CVITP where the FES might have been expected to say something but was silent. These omissions create uncertainties around the federal government’s long-term commitment to the CVITP.

The main source of these uncertainties is the assumption Canada Revenue Agency officials are probably making that the futures of automatic tax filing and the CVITP are inextricably linked. As automatic tax filing becomes the norm for low-income Canadian residents, they may believe the CVITP could be substantially scaled back.

Working from these omissions, this article offers three scenarios for future CVITP funding together with their respective impact on CVITP operations. It also assesses the likelihood of each scenario based on current political realities.

The most probable of these three scenarios will prove disruptive to the CVITP’s future operations. Even so, like the other two scenarios, it suffers from a fundamental flaw inherent in the advancement of automatic tax filing as currently envisioned by the federal government.

Read here to learn more about what all this means for the CVITP as well as for non-filers who were the original focus of the automatic tax filing initiative.

Every fall, the Department of Finance Canada provides an update informing the public about the state of the federal government’s finances and key economic developments. The Fall Economic Statement (FES) for 2024 was issued on December 16. Intriguingly, it touched on the issue of filing the income tax and benefit returns of low-income Canadians.

The articles in this two-part series tackle both what the FES said and what it did not say about this subject as the government’s omissions were as relevant to the CVITP as its treatment of the filing of returns for low-income Canadians.

The first article presents and comments on what the FES had to say on this subject. The FES discussion was limited to advancing its agenda for the automatic filing of low-income Canadian’s income tax and benefit returns. This article highlights the relevance of this agenda for the CVITP. It also lays the foundations for the second article, which speculates on some reasons why the CVITP may suffer from weak growth over the next few years.

Host organizations need to collect anonymized client data both to show the impact of their CVITP clinic to their stakeholders and to provide the information needed to improve the CVITP service they are offering.

There are two ways that a host organization can get this data: ask the CRA for it or collect it independently. Last year, we argued the case for why host organizations should ask the CRA for their anonymized client data.

In this article, we recount our own experience earlier this year of helping some host organizations in our area to ask the CRA for the data. We outline some lessons we learned from that experience.

While we were successful in getting the CRA to share some of its data, read here about the problems we encountered interpreting this data. Our experience suggests this approach to getting data would be useful only for a limited number of host organizations. It provides host organizations with one possible benefit but not the full range of advantages one could expect from the data currently collected by the CRA. For host organizations that want the full range of advantages from the data, the best approach is to collect it themselves. Advice on this latter approach will be the subject of a future article.

In a recent article on the CVITP participation rates of those living in poverty, we noted that “New Brunswick has the best participation rate, with 43.4% of the province’s poor receiving CVITP services. At 17.4%, Ontario has the worst participation rate among the provinces, well below the rate for all the provinces combined (24.3%).”

The purpose of this article is to explore some of the reasons for these wide divergences. To help find some of the reasons, we compare the two best performers, New Brunswick and Prince Edward Island (PEI), with the two weakest performers, Ontario and British Columbia (BC).

First, we dismiss a couple of reasons we think are not relevant. Next, we analyze the Canada Revenue Agency (CRA) CVITP data for 2021 at the provincial level. Here we discover three important differences between these high and low performing provinces. Then we look at the provincial level data in 2022 and 2023. We want to see if there have been changes since 2021 in these three areas which might significantly improve the CVITP participation rates of the poor performers relative to the strong performers.

Finally, we link these differences with the expected results of the CRA’s pilot grant program. We argue that the developments in these areas prove the pilot did not achieve two and arguably three of its four expected results. (No CRA data has been made public which allows for an assessment of the fourth area.)

Read here about the three differences between the high and low performing provinces in 2021, how these differences evolved between 2021 and 2023, and why we believe they demonstrate that the CRA’s pilot grant program has been a disappointment.

Our work is based on the connection the federal government has drawn between poverty reduction and the CVITP in its 2018 Poverty Reduction Strategy. Specifically, this strategy recognizes the important role the CVITP plays in providing access to the many federal (and provincial/territorial) benefits designed to reduce poverty.

Following the publication of the Strategy, the Poverty Reduction Act was adopted as law by Parliament in 2019. Among other things, the Act requires the federal government to set up a National Advisory Council on Poverty. To date, the Council has produced five annual reports (2020 – 2024). Yet nowhere in these five reports is any mention made of the CVITP. We find this surprising.

In its reports, the Council urges improved access to existing benefits. Yet the Council never considers the role that the CVITP currently plays in facilitating access to those benefits, the challenges it faces in doing this and its weak performance in meeting these challenges.

Learn here why we think the Council should not remain silent on the only federal government initiative designed to help those living in poverty get the benefits to which they are entitled. Read here what the Council should instead be doing.

There are great disparities in vulnerable Canadians’ access to CVITP services across Canada. This shows up clearly in the different rates of participation in CVITP services between the provinces.

In this article, we look at the 2020 provincial poverty data Statistics Canada estimated using its Market Basket Measure or MBM. (At that time, Statistics Canada had yet to establish a separate MBM for the territories.) We compare this data with the CRA’s data on the number of CVITP clients served in each province during the 2021 tax filing season. From this, we calculate the percentage of those living in poverty who were served by the CVITP. (We use the generous assumption that all individuals served by the CVITP in 2021 were living in poverty in 2020.) This gives us what we call CVITP participation rates by province.

These rates vary substantially between the provinces. See here how your province ranks in comparison to the other provinces in providing CVITP services to those living in poverty.

In a series of three articles, we look at three initiatives other than the CVITP that the Canada Revenue Agency (CRA) seems to be focusing its efforts on to reach low and modest-income Canadian residents. We show why these initiatives presently show less promise than the CVITP in tackling the fundamental problem of helping a greater percentage of Canada’s impoverished residents access the benefits to which they are entitled.

In the first article of this series, we looked at the CRA’s non-filers benefits letter initiative. We argued that the results are insignificant, even questionable and bear no comparison with those obtained by the CVITP when it comes to assisting those living in poverty.

In the second article, we looked at SimpleFile by Phone, the CRA’s automated phone service for filing returns which has operated since 2018 under a different name, File My Return. We concluded that the results are insignificant, especially when compared with those produced by the CVITP. It is also far less cost efficient in producing results than the CVITP. Furthermore, we showed why the service does not live up to its stated promise of helping Canadians who have not filed in the past to access their benefits.

In this third article, we look at the CRA’s long awaited pilot for automatic tax filing, SimpleFile, which was launched in July 2024. Learn here why we think that, unlike its billing, filing a return under this new method is not automatic, the process is not “simple” to complete, this new method will not reach non-filers as originally intended, and the launch of the pilot is not well timed so is likely to perform poorly.

In a series of three articles, we look at three initiatives other than the CVITP that the CRA seems to be focusing its efforts on to reach low and modest-income Canadian residents. We show why these initiatives presently show less promise than the CVITP in tackling the fundamental problem of helping a greater percentage of Canada’s impoverished residents access the benefits to which they are entitled.

In the first article of this series, we looked at the CRA’s non-filers benefits letter initiative. We argued that the results are insignificant, even questionable and bear no comparison with those obtained by the CVITP when it comes to assisting those living in poverty.

In this second article, we look at SimpleFile by Phone, the CRA’s automated phone service for filing returns which has operated since 2018 under a different name, File My Return.

Learn here why the results are insignificant, especially when compared with those produced by the CVITP. It is also far less cost efficient in producing results than the CVITP. Furthermore, we show why the service does not live up to its stated promise of helping Canadians who have not filed in the past to access their benefits. It is important to recognize the limitations of SimpleFile by Phone because, as will be seen in the third article, this is also part of the CRA’s pilot aimed at launching automatic tax filing.